Like most children, I took my father for granted. It was only when I became a woman, in the 1960’s, that I realized how different he was from most men born in the early 1900’s. And how lucky I was to have a father who never even considered treating his daughter differently than he would have treated a son.

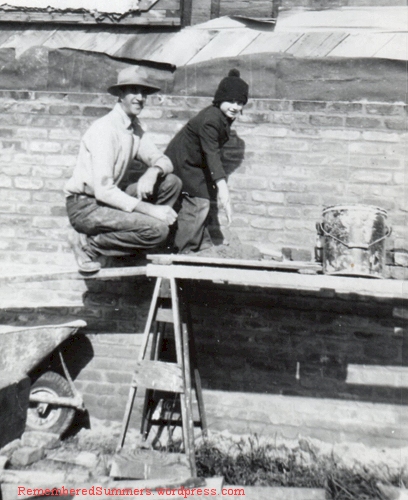

My father leveling a construction site, with me (very briefly) in his lap. He built the two houses in the background with his own hands, in 1933. As far as I know they’re still standing.

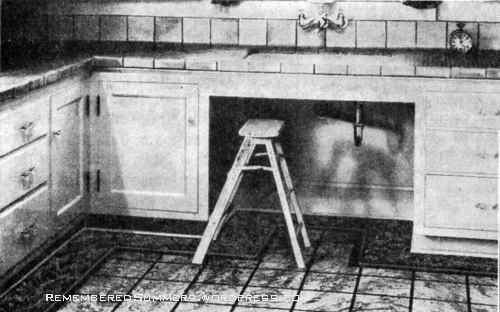

He did manual labor all his life, and, being a housemover, he had to know everything about building a house: laying the foundations, doing the wiring and plumbing, carpentry, framing and finishing, putting on a roof, installing floors and kitchens and baths, stuccoing and painting, even laying bricks and paving the driveway. He assumed his daughter would also need to know these things. Once, he let me “help” him drive a steamroller!

My father showing me how to lay a course of bricks on the front of a building. (The bricks are level; the camera was tilted.)

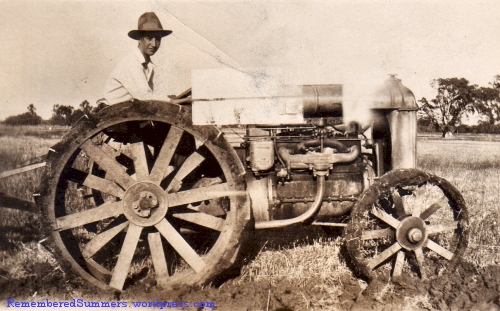

Unlike most modern children, I could see my father working. He didn’t disappear in a suit at 7:30 each morning and return just before I went to bed. His clothes smelled of paint or cement or new-sawn wood or creosote. Sometimes they had a whiff of car oil or gasoline, because he could also take an engine apart and put it together again. (A teenager in 1920, he started with model T cars and early tractors, so he mastered their principles while they were relatively simple machines.)

My father on an early tractor. He had learned to plow with a horse, so he loved “modern improvements.” At the end of a long day, he didn’t have to shovel out the barn anymore.

He taught me to use and care for tools correctly, to drive a nail with two strokes (“One to set it, one to drive it,”) to paint walls and patch holes, to clean my brushes properly, to take pride in my work and in not taking shortcuts; to plan a job and do it safely. He expected me — a girl — to be responsible, fearless, confident that I could learn to do whatever had to be done. [When I attended a woman’s college, I found these skills much appreciated in the drama department. I knew how to use tools, and I was willing to get dirty. And, because I was afraid of heights, I specialized in stage lighting, spending hours climbing ladders. My father taught me to overcome my fears, not be limited by them.]

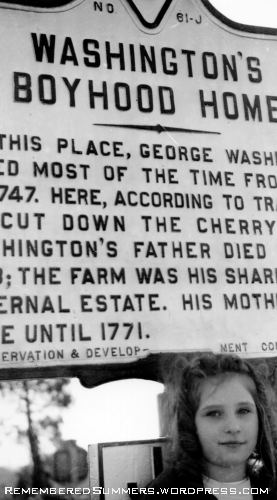

I think my father took this picture, because I always felt this delight when he came home from work.

I think the only time I really disappointed him — although he didn’t say anything — was when he discovered that I didn’t share his appreciation of the internal combustion engine. He must have been looking forward to teaching me how to clean a carburetor, but I only lasted a couple of nights. When I asked him to teach me to change my own oil, he said, “By the time you clean up and wash your clothes after crawling under the car, you’d be better off taking it to a gas station.”

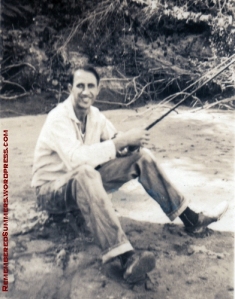

Nevertheless, he taught me to fish — and clean the fish and cook it — and to shoot. I was about nine years old, able to handle the .22 rifle, but he said the recoil from his deer rifle would be too much for me. Nevertheless, he taught me to load it and unload it — if you’re not going to be afraid of guns, you need to know when they are and aren’t safe to handle.

When we visited him on a work site, sometimes we’d have a picnic lunch with him. Once, he caught a gopher snake and brought it to me, so I could watch it curving back and forth, over one stick and under another. He showed me how beautiful it was, and how to tell a “safe” snake from a rattler. He made sure I knew that not all snakes are bad — that some are very useful and deserve our respect. He showed me a nest of baby mice on another occasion (uncovered while clearing a field) — but I found their hairless, translucent skin repulsive. I could tell, however, that he thought they were tiny miracles; he was sad that they had been stripped of their safe little home. He was very careful with them. He also taught me not to pick wildflowers. When I insisted on taking a bouquet home with us, he remembered to show me they were wilted and no longer beautiful that night. I never picked wildflowers again.

Since all my uncles — and most of their friends — were in the building trades, my father built the house I grew up in, with some help from pals and brothers who were plumbers, tile setters, carpenters, etc. Down in the cellar of this little vine-covered cottage, I found a heart inscribed in the concrete, with my parents’ initials and the date of their marriage: 1933 — the depths of the Depression.

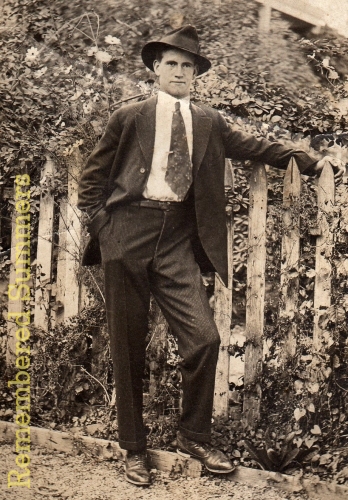

My father came from a family of six-footers, and he was not only extremely tall, but freakishly thin all his life. When Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes was described as very thin but exceptionally strong, with “sinewy forearms,” I had no trouble believing it. Once, we found an old tuxedo my father had worn when he and my mother went out dancing, decades before I was born. “On the day I married your mother,” he told me, “I was six feet four inches tall, weighed one hundred and forty pounds, and thought I was a helluva good-lookin’ fella.”

In spite of his long, thin body, my father was very strong, and was still doing manual labor in his sixties. The most he ever weighed was 172 lbs.

His friends sometimes used him as a unit of measurement, as in this photo, where his arm span shows the size of a giant tree in Yosemite.

This photo of my parents and me in front of their small house in Redwood City implies more prosperity than we usually experienced. My mother, decked in a fur stole, had continued to work as a secretary during the first years of their marriage — a two-income couple.

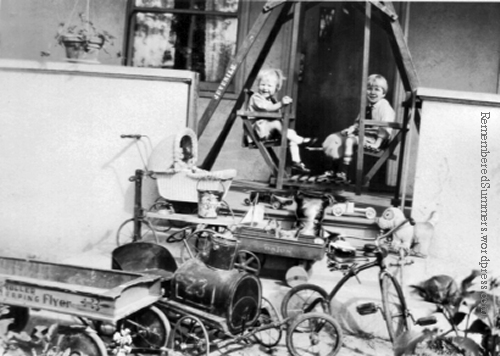

Happy times. My father liked to sing, “Just Molly and me, and baby makes three; we’re happy in My Blue Heaven.”

My arrival, 12 years after they wed, came as a pleasant surprise for two people over forty who had given up hope of having a family. But it undoubtedly put a strain on their budget, as did my mother’s cancer surgery a few years later.

My father owned a small house-moving business; in the post-war years when highways were being built and downtown areas were being improved, there were plenty of houses that needed moving. When someone’s home was in the way of a new freeway, their wooden frame house could be jacked up off its foundation, put on “Blocks” and wheels, and towed to a new location. This was skilled work, since no one wanted big cracks to form!

My father is the tall figure on top of the house. Telephone and electric lines sometimes had to be cut temporarily or moved out of the way so the roof would have clearance. A man on the roof also watched for problems — a position that was doubly dangerous. My father did it himself.

In many construction trades, no work can be done when the weather is too wet. As a child, I remember visiting my Uncle Monte (who drove a bulldozer) on a weekday in the winter. I expected him and my father to be happy, as if a rainy day was like a day when you didn’t have to go to school, but supporting a family through a wet winter was no “holiday” for working men. Every morning, my father’s foreman and best friend, Walter, would drink a cup of coffee at our kitchen table while they planned the day’s work.

I remember a long, rainy December when the morning meeting was grim. Christmas was coming, we had medical bills to pay, and the ground was too saturated for housemoving. Walter suggested that, as there was no work, they should call all the men and tell them not to come in till next Monday, if the rain broke by Saturday. My father said, “We need to find something for “X” to do; they just had a baby. Tell him to come in tomorrow and service the tractor and the truck.” These were jobs my father, himself, normally did on rain days, to save money. “And “Y” needs some work; his wife is in the hospital for an operation. Give him a day and a half; tell him to come in and clean up the yard (sorting lumber, etc.)” My mother, listening, was furious — we were looking at a pretty lean Christmas, ourselves. She called this “playing the Big Shot.” It was true that my father was generous to a fault. But he also felt a responsibility to his men.

After my mother died, in spite of her bitter misgivings about him, my father took good care of me. He trusted me to use my common sense, and he believed in me. (I was never a “latch-key kid,” because we never locked our house.) He showed me — by example, working with me — how to do laundry, and clean the floors and wash dishes; he taught me to cook, and he loved to cook, himself. When I was little, he made me pancakes in the shape of airplanes and cats; now, he cooked fabulous spaghetti bolognese, taught me to love vegetables and fresh fruit (as he did), and, on the occasions when we could afford a porterhouse steak, he practically danced around the kitchen, singing:

“[A] turn to the right, a little white light, [I hurry] to my Blue Heaven. Just Molly and me, and baby makes three, We’re happy in My Blue Heaven. . . .” He sang very well. And he always gave me the tenderest part of the steak. because he wanted me to love it as much as he did.