“Through the turnstile to a land of Adventure!” Ad for the new Piggly Wiggly grocery stores, The Delineator, January 1929.

Through the Turnstile to a Land of Adventure

The sale this month [January 2015] of Safeway stores to Cerberus Capital Management, which also owns the Albertson’s supermarket chain, reminded me of this advertisement from January 1929, when the supermarket was a new idea. It shows a woman with a market basket who has passed “Through the turnstile to a land of Adventure:” a Piggly Wiggly supermarket.

At the start of the nineteen twenties, most people had never seen a grocery store where shoppers selected their own produce and canned goods.

In the early 1920s, the customer approached the counter, made a request, and the clerk selected the merchandise for the shopper. Much of the merchandise was kept behind the counter. [In France, in 1978, I selected my own apple from a display at an open market, and was immediately scolded by the furious proprietor. Customers did not select their own fruit! One could look, but not touch, and the best produce was reserved for regular customers.]

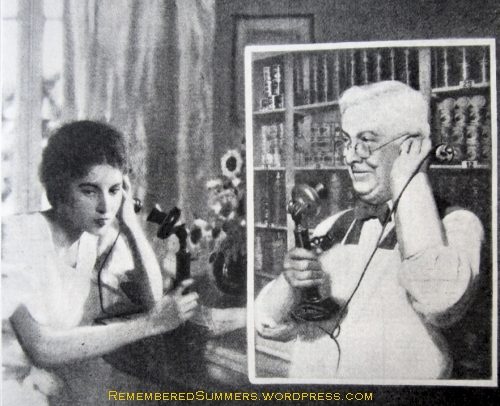

Ordering groceries by telephone. Ad for Fleischmann’s Yeast, Delineator magazine, August 1924. The grocer wears a suit vest, an apron, and sleeve protectors.

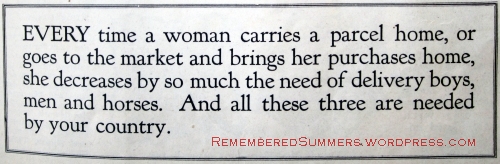

People wealthy enough to have a telephone ordered groceries this way and had them delivered. This was such a common practice that, during World War I, the government asked women to go to the store and pick up their own groceries, to free up manpower (and “grocery boys”) for military service.

Piggly Wiggly Advertises a Revolution in Grocery Shopping

The first Piggly Wiggly store, opened by Clarence Saunders in 1916, in Memphis Tennessee, had to introduce its customers to self-service shopping.

“There were shopping baskets, open shelves, and no clerks to shop for the customer – all of which were previously unheard of!” — Official Piggly Wiggly Site. Click here to read the Company History.

In 1929, shoppers had to be taught how to shop at a Piggly Wiggly; they also had to be convinced that self service was better than being waited upon by clerks. [I am still less than thrilled when I have to do self-checkout at Home Depot and the supermarket. I can’t help thinking about all the jobs that have been lost, how hard it is to get help while shopping, and how often the checkout does not go smoothly.]

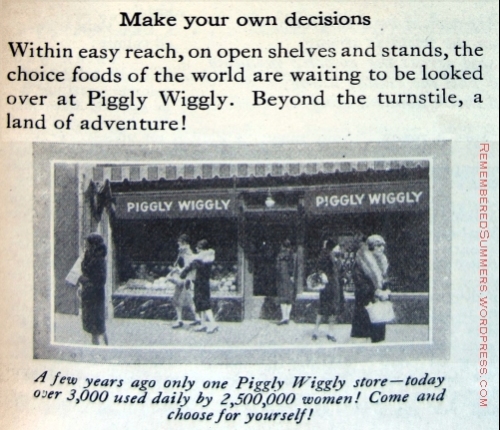

Piggly Wiggly ad, Jan. 1929. By this time, the chain had over 3000 stores “used daily by 2,500,000 women!”

The full-page advertisement showed shelves of canned goods accessible to the shopper, who could handle and inspect the merchandise:

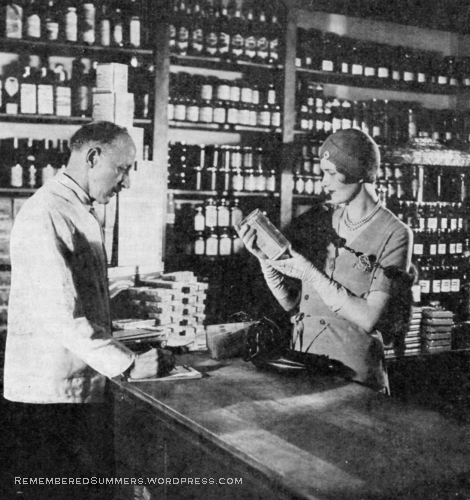

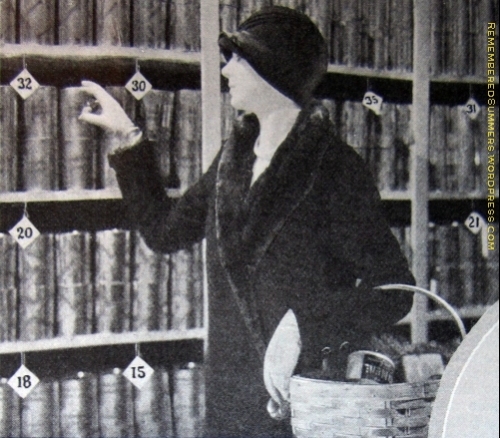

A Piggly Wiggly shopper with a basket selecting her own purchases. Allowing the customer to handle the merchandise was still a new idea in this 1929 ad. [Are the diamonds with numbers Piggly Wiggly’s square price tags, mentioned elsewhere in the ad?]

Elsewhere, the ad has to convince the shopper that she is better off without having a clerk to help her:

“Women like to tell their friends about this unique method of shopping. They enjoy discussing its advantages. Old customers send us thousands of new ones every week.

“In a few swift years women have made this plan of household buying a nation-wide vogue.

“With their new, wide knowledge of real values the women of today want to choose for themselves. When they shop for foods, they want no clerks to urge them. To them, this special plan is an easy way to give their families delicious meals at less expense.” — text of Piggly Wiggly Ad, January 1929.

The man behind the counter, Armour meat Ad, Ladies’ Home Journal, July 1917. Grocery clerks like him would be eliminated in the new supermarkets.

“Famous packages, familiar jars and cans, fresh inviting fruits and vegetables — each item with its big square price tag, at Piggly Wiggly. And no clerks!

“You linger or hurry as you please. Take what you like in your hands, examine it at leisure. You compare prices, make your own decision — uninfluenced by salesmen.”

Subtle Advertising Language

Students of advertising should study the vocabulary of this ad. Certainly, the ability to see the price of every item and to compare them is a help to careful budgeting. But there is also a subtle appeal to the independent “woman of today” who can “choose for herself” and make her “own decisions.” They are freed from high-pressure salesmen (the clerks in all these ads are men) and from the humiliation of having to ask the clerk for something cheaper. Also, in a world where shopping was still a daily chore, words like “linger” and “leisure” and “vogue” are emotionally powerful.

Of course, “Consistently lower prices are assured by our unusual and economical plan of operation.”

Which brings me back to the Safeway-Albertson’s merger under Cerberus Capital Management; according to Andrew S. Ross, writing in the San Francisco Chronicle:

“There are elements of deja vu for Safeway. In 1986, it was taken private in a $4.25 billion leveraged buyout by led by Kohlberg Kravis Roberts. The deal worked out wonderfully for KKR, which made $7.2 billion on its initial $129 million investment when it sold its stake in 1999. Not so much for the tens of thousands of Safeway employees who lost their jobs as a result of mass store closings and other cuts.”

No gains without pains. . . . But let’s return to the 1920’s. Imagine stores without endless aisles wide enough to accommodate shopping carts (yet to be invented — or needed). There were no frozen foods. The same fruits and vegetables were not available all year round. There were no scanning devices, or universal price codes. There were no stickers on apples and pears, and no wax on cucumbers or tomatoes. It was safe to eat a raw egg or a medium rare hamburger. Cellophane was a new invention, not used for wrapping foods until the mid-1920’s. Imagine a time when entering a store through a turnstile was an adventure! Never mind that the new turnstile was an anti-theft device. “Just walk through the turnstile and help yourself!” How delightful.